Introduction

After the end of the Second World War, Toyota Motor Co. set a daring objective: Catch up to America within three years. Back then, Japanese automobile manufacturing lagged far behind American powerhouses. Few outside of Japan took it seriously.

But then Toyota did it.

Production engineer Taiichi Ohno set out to minimize as much inefficiency within the manufacturing process as possible. He recognized the company’s habit of stockpiling excess inventory was hurting their productivity and that “pushing” cars down the assembly line before stations were ready to work on them caused blockages, resulting in wasted time and half-finished products.

Ohno cut inventory down to the bare minimum and created a new system relying on kanban—signboards—to ensure a smooth flow of products down the production line, allowing Toyota’s factories to process more orders, faster. The result was the Toyota Production System (TPS), often referred to as “lean” or “just-in-time” (JIT) manufacturing. The TPS quickly became the gold standard for manufacturing and was soon emulated by factories worldwide.

In the early 2000s, software development was struggling. Engineering teams had an inventory problem of their own—huge backlogs of work, which resulted in half-finished products, unpredictable delivery dates, and burnt-out workers. Not unlike the postwar Japanese automobile industry. Inspired by the Toyota Production System, David J. Anderson created the Kanban Method. Little did he know the Kanban tool would become a ubiquitous tool for modern teams.

What is Kanban?

In Japanese, kanban (看板) means “signboard” or “signal card.” In a factory environment like Toyota, workers use these signboards to signal upstream stations on the production line to produce more. This ensures that each station only makes more products when the next station is ready for new goods.

The Kanban Method devised by David J. Anderson—which we’ll just call Kanban (capital K) from now on—applies the manufacturing theories of the Toyota Production System to knowledge work, particularly software development. Simply put, “Kanban is an approach that drives change by optimizing your existing processes,” explains Anderson.

Kanban is an approach that drives change by optimizing your existing processes.

–David J. Anderson, creator of the Kanban Method

Anderson’s methodology is based on four main ideas:

- Visualization: The most iconic feature of Kanban is the Kanban board. The Kanban board is a system of visual control that allows teams to map out their workflows from start to finish. Different columns mark different stages in the process, while cards (originally index cards or sticky notes) show tasks moving through the system. At its most basic, a kanban board could look like this:

- Constraints on work-in-progress: The more you take on at once, the slower your work goes—and the more likely something is to go wrong. The amount of work-in-progress in a system is directly proportional to risk. This also applies to “batch size” (i.e., the size of one task). Larger batches comprising many steps take much more time to accomplish and are more prone to failure. Kanban uses small batch sizes to speed up cycle times, reduce risk, and gain frequent feedback, which results in an improved product. By trying to do fewer things at once, teams do better work faster.

- A pull system: The pace of production is not set by the fastest stage in the process but the slowest. If you can build five cars a day but only have the resources to paint two, you will only be able to produce two cars a day. It’s more efficient to build cars at the rate you can paint them, so you can sustain a consistent pace of production. “New work is pulled into the system when there is capacity to handle it, rather than being pushed into the system based on demand,” says Anderson.

- Continuous, incremental improvement: Continuous improvement, or kaizen, is built into the TPS. In fact, kanban is a key enabler of kaizen. As Taiichi Ohno explains, “The two pillars of the Toyota production system are just-in-time and automation with a human touch or autonomation. The tool used to operate the system is kanban.” The goal of Kanban is for teams to continually improve their processes and become more efficient over time.

Anderson first tested Kanban at Microsoft in 2004, with great success. After some further experiments at other companies, he began to share his findings. Soon, the idea took off. It was quickly adopted by tech companies like Yahoo! and spread around the world. The success of the method prompted Anderson to codify it in his 2010 book, Kanban.

How does Kanban work?

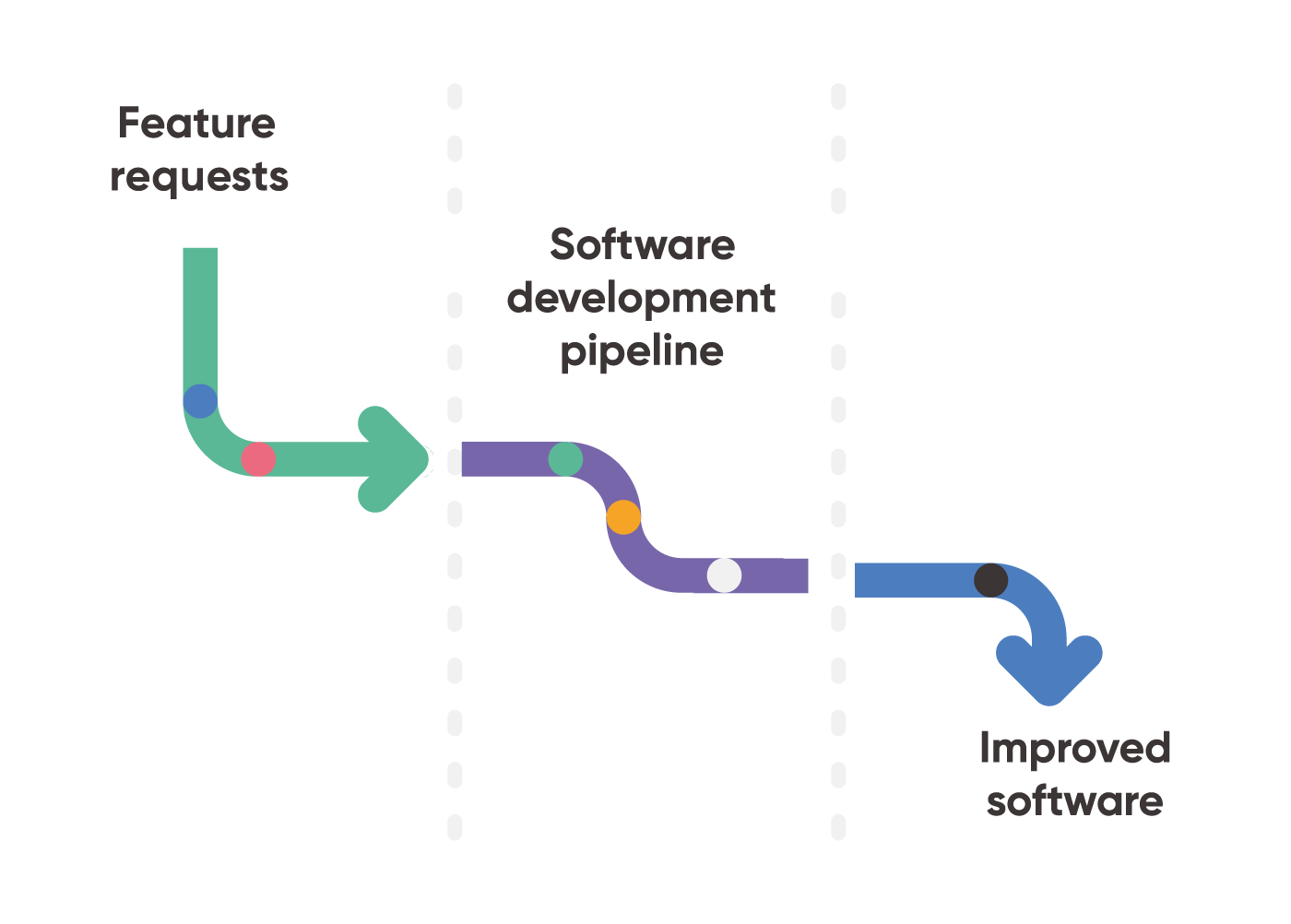

Kanban is a mirror. It reveals your processes as they are, not what you think they are or want them to be. While software development and other kinds of knowledge work may not physically move along a factory production line, projects do move through production stages from beginning to end—this is what Kanban illustrates. In software, this is known as the development pipeline.

Kanban begins by mapping these stages and figuring out how much work-in-progress (WIP) is at each phase, using a Kanban board. Here’s an example of what such a board could look like:

As teams begin to make incremental changes to their workflows, the Kanban board reflects these changes back to them. One key first step in Kanban is to limit the amount of work-in-progress (WIP) in the entire system. This was one of Taiichi Ohno’s most important observations: Excess inventory slows work down and results in a worse final product. Anderson recognized that this principle applies just as much to virtual work as physical manufacturing. In a knowledge work environment, more WIP incentivizes multitasking—which is more inefficient and ineffective than single-tasking—and draws out the time between feedback cycles.

Less WIP allows team members to work on one thing at a time and complete production cycles more quickly. These shorter iterations allow for faster feedback, meaning that teams can correct problems quickly and design quality into products from their earliest stages. In addition to improving efficiency, reducing WIP helps reveal where bottlenecks are. For instance, visualizing your team’s work on a Kanban board may reveal that you have the capacity to design and build five new features simultaneously but only test two—meaning that testing is your bottleneck.

Once teams can identify their bottlenecks, they can begin to make small changes to make the most of them. This is where the pull system comes in. Teams can strategically implement queues so that a bottleneck pulls in new work from earlier stages, when it’s ready, not when earlier phases push new work along. As a result of these improvements, the bottleneck may actually move, and the process of identifying and optimizing it begins again—that’s the philosophy of kaizen in action.

Why Kanban?

Kanban is easy to start

“A strength of Kanban is that it does not start with an anxiety-inducing upheaval,” writes Kanban blogger David Peterson. “It starts simply by mapping out the existing process exactly as it stands.” This makes it easy for teams to start implementing Kanban. Crucially, it also reduces fear around change. “Asking people to change their behavior creates fear and lowers self-esteem, as it communicates that existing skills are no longer valued,” writes Anderson. By contrast, Kanban lays a foundation of trust, which enables ongoing, incremental improvement.

Kanban uses simple methods to promote sustainable improvement

We know from studies of human conduct that observation can be a powerful driver of behavior change. In one Dutch study, households with highly visible electric meters used 30 percent less power than their neighbors whose meters were located out of sight. They adjusted their habits in response to visual feedback. Similarly, “Kanban will reveal opportunities for improvement that do not involve complex changes to engineering methods,” says Anderson.

Kanban is context-dependent

Kanban does not demand conformity. Rather, the method is adaptable to diverse practices, team structures, and goals. Since Kanban relies on simple changes to drive sustained improvement, these practices can be adopted in almost any work environment with little disruption. Teams or individuals can use Kanban in vastly different ways and still experience the same benefits of shorter production cycles and better quality results.

Kanban creates a consistent, reliable production pace

By enabling teams to track, understand, and gradually improve their workflows, Kanban helps practitioners establish a regular production cadence. Regular, high-quality releases improve customer satisfaction and build trust with other departments and stakeholders. A sustainable work pace is also important for teams’ overall well-being—it prevents people from scrambling to meet last-minute deadlines at the cost of their mental and physical health.

Common Kanban misconceptions

Kanban is not a software development lifecycle methodology (SLDC)

Unlike other systems, “Kanban is not a software development lifecycle methodology or an approach to project management,” says Anderson. “It requires that some process is already in place so that Kanban can be applied to incrementally change the underlying process.” Teams use Kanban in tandem with their existing SLDC and project management approaches to refine and optimize them.

Kanban is not just a visual control system

“The way kanban boards make WIP visible is striking, but it is only one small aspect of this approach,” writes Don Reinersten in the foreword to Kanban. The board is a tool that enables teams to reduce their batch size, implement a pull system, and strive for continuous improvement. These techniques result in faster production cycles and better-quality output.

Kanban isn’t just for enterprise software or IT

Kanban can be used for all kinds of work. That’s the beauty of Kanban: It’s highly malleable to different projects, workflows, and team structures. In fact, it’s so simple to learn that some families use the Kanban system to help kids manage chores at home. Anyone, individual or team, who produces some kind of output—be it software, blog posts, or even clean laundry—can benefit from Kanban and customize their board to their needs.

Kanban in action

Before we delve into the nitty-gritty of the Kanban Method, let’s review some key definitions.

Kanban concepts

- Backlog: Holding column for all work—upcoming projects, requests, and ideas—for teams to complete.

- Input queue: Holding column for work that’s ready to be started. Teams select tasks to prioritize from the Backlog and move them here.

- Work, work-in-progress (WIP): Any task that needs to be completed. These fall into two main categories: Planned work, such as business and internal projects, and unplanned work, sometimes called “firefighting,” which occurs when something breaks unexpectedly.

- Flow: The process of work moving through stages, from initiation to completion.

- Handover: Any instance of work moved from one person to another. This usually occurs between stages. For instance, a developer “hands” her code over to QA to be tested.

- Lead time: The amount of time from beginning to end of a process, or how long it takes a task, once started, to move through all stages to completion.

- Touch time: The amount of time spent working on a given task, not including time spent queuing or waiting.

- Bottleneck: The slowest stage in a production process. This sets the pace of every other production step.

- Cadence: The regular rhythm or “heartbeat” of production. Individual steps have their own cadence, as does the process as a whole.

- Throughput: The amount of work that passes through the system, from start to finish, in a given time period.

The Kanban Method

David J. Anderson’s Kanban Method takes concepts from just-in-time manufacturing and applies them to the production of intangible goods. While it was initially designed for software development, Anderson’s approach uses simple principles that can be adapted to a wide range of contexts—not just software. In this section, we’ll examine each of these principles in detail.

1. Mapping the value stream

The essence of starting with Kanban is to change as little as possible.

–David J. Anderson

In order to improve your processes, you need to first understand them. That’s why the first stage in the Kanban method is to map your processes, or “value stream,” as Anderson calls it. This is where the Kanban board comes in.

Here’s how it works: Teams use columns on a Kanban board to represent different stages in a workflow. How they define these columns depends on the nature of the work they’re completing—a development team’s columns will be very different from a marketing team’s—but all boards have at least three: An input queue to collect work that hasn’t yet been started (to do), a column to show work in progress (doing), and a column to show completed work (done). Most teams will also have a backlog of work to collect new tasks—once these are scheduled and prioritized, they can be added to the input queue. Teams will also typically add columns in the middle to capture the phases that work goes through from initiation to completion.

While columns show the different steps in a workflow, cards track the movement of different tasks through the process. Depending on the board’s purpose, cards may be color-coded to represent different projects, kinds of tasks, or even the size of the work. If several projects are occurring simultaneously, some teams may use rows, known colloquially as “swim lanes,” to differentiate between projects.

2. Limit work-in-progress (WIP)

WIP is the silent killer.

–The Phoenix Project

The second stage of the Kanban method is about limiting WIP so that no one has to multitask, but everyone has something to do—the optimal level for production speed and quality. To reach this level, teams need to limit the amount of work that enters the system in the first place and also the amount of work-in-progress at each step. They do this by setting limits on columns—teams limit the input queue as well as each column in the process. For instance, if you only have the capacity to test two new features at a time, your testing column should have a limit of two.

Reducing WIP also has the benefit of revealing where bottlenecks are, allowing teams to optimize their workload to match the pace of the bottleneck. The goal of Kanban is to ensure that bottlenecks are operating at capacity—meaning they are busy but not overwhelmed. Non-bottlenecks should have slack time, which will allow them to complete their work efficiently and still have time left over for learning and improving their skills, which will benefit the team in the long run.

3. Measure and manage flow

If the Kanban system is flowing correctly, the bands on the chart should be smooth and their height should be stable.

–David J. Anderson

The simplest way to determine whether the Kanban system is working correctly is to watch your flow. Are the number of tasks across columns generally stable? It’s okay if your columns aren’t even to begin with—everyone needs to start somewhere. What teams should watch for is whether work balances out over time. If column heights don’t smooth out over time, it might be necessary to revise WIP limits or add other interventions to improve flow.

4. Make process policies explicit

Thinking of process as a set of policies is a key element of the Kanban method.

–David J. Anderson

In order to ensure a consistent flow of work, everyone needs to understand and support the process. Anderson conceives of the process as “a set of policies that govern behavior.” These policies, which are typically under the control of the team’s manager, include things like:

- How to prioritize items from the backlog

- What needs to be accomplished before work can progress to the next step

- What WIP limits are

- Rules around time-sensitive or expedited requests

- Handling blockages and other issues

- Etc.

It’s up to the leadership of a team to make sure everyone knows what these policies are and follows them. One way teams can make their policies explicit is to write them into the Kanban board itself—for instance, teams can include their WIP limits on each column, so it’s obvious how many tasks should be in progress at a given moment. As teams learn from Kanban and refine their processes, they should continuously update their policies accordingly.

5. Use models to recognize improvement opportunities

I would further encourage you to expand your thinking and look to a wider variety of models that enable and empower teams to generate improvements.

–David J. Anderson

Kanban is a process of continuous learning. When teams first adopt Kanban, they’ll be able to refine and optimize their processes just by putting the principles of Kanban into practice. Once teams have been performing Kanban for a while, however, these opportunities for improvement may be less obvious. In order to keep advancing, Anderson suggests teams look at other models and methodologies to see what areas of improvement they reveal. While we won’t be discussing any of these models in detail, advanced Kanban practitioners may benefit from learning about the following:

- Theory of Constraints

- Systems Thinking

- Variability (as conceptualized by W. Edwards Deming)

- Muda (waste) in the Toyota Production System

Choosing a Kanban tool

To begin Kanban, you first need to decide on your setup. Though Anderson initially conceived of the Kanban board as a physical tool, in the ten years since he published his book, the workplace has changed in significant ways: Remote work is on the rise, and teams are often spread between cities—if not continents. “For teams that are distributed geographically, or those who have policies that allow team members to work from their homes one or more days per week, electronic tracking is essential,” writes Anderson. Digital boards are accessible anywhere with a Wi-Fi connection, making them an ideal, flexible solution for modern teams.

Virtual Kanban boards provide numerous other benefits. They solve the problem of being able to reference old tasks and projects—old cards get archived, unlike physical ones, which tend to get lost or thrown away. Digital Kanban boards are also often integrated into project management tools like Backlog, making them ideal for managing complex projects. For instance, Backlog’s Boards feature makes it easy for users to provide context to their Kanban boards by adding comments or attaching documents and screenshots. Team members can also easily switch between views so they can see their entire team’s work or just focus on their own tasks.

Whatever tool you choose, make sure it’s something your team likes and wants to use—this will motivate them to embrace Kanban and drive process improvement.

How to set up your Kanban board

Once you’ve selected a tool, it’s time for the fun part—building your board. When you first start using a Kanban board, the goal is just to get visual feedback on what you’re doing right now. Later on, you can implement column limits and queues to help control the flow of work through the system, but the first stage is just to map your process. Here’s how:

Kanban board setup checklist

- Identify a workflow

- List the kinds of work it processes

- Create a process for adding new work to the system

- Define classes of service

1. Identify a workflow

Depending on the kind of work you do, your board might be basic or highly sophisticated. The only “right” way to set up a Kanban board is to accurately reflect the work you actually do—your workflow.

Define start and end points

If you’re part of a larger organization, there’s only so much you can control. It’s important to recognize this when implementing Kanban. Your Kanban board should begin where you, as an individual or team, take ownership of a process and finish where your control ends.

Map the steps in your process

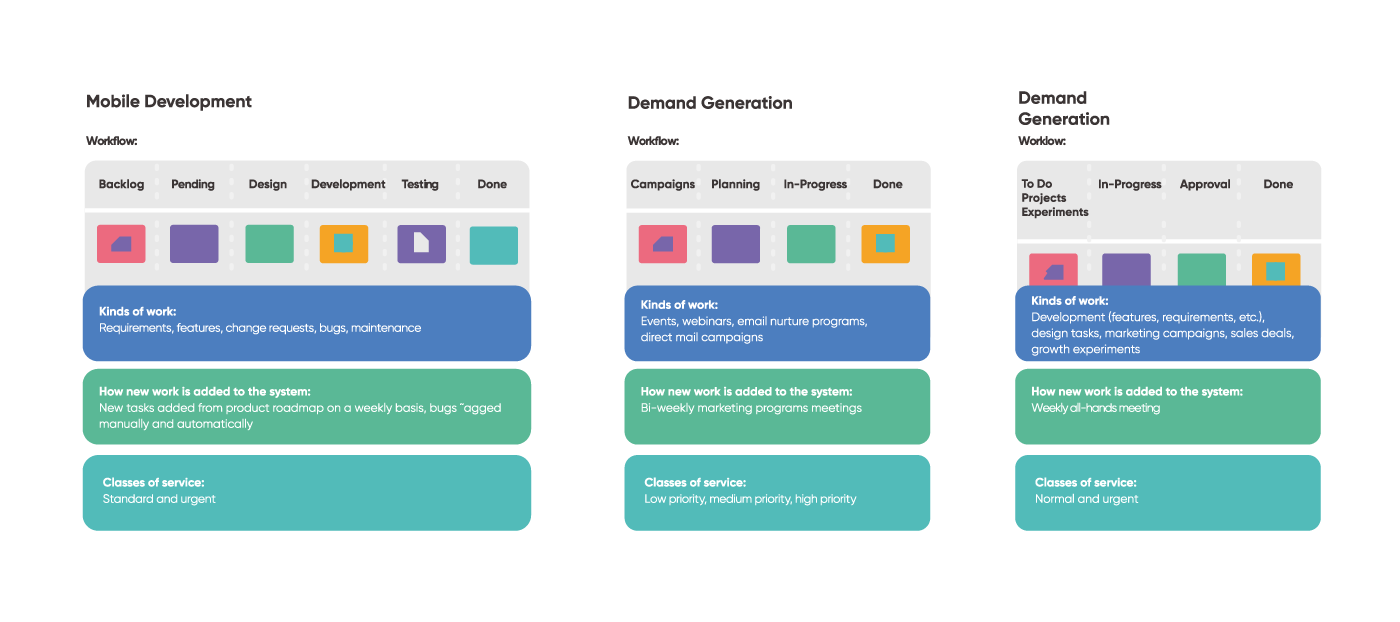

Once you’ve identified the start and end points in your process, it’s time to break down the steps that make up your workflow—what will become your columns. Handoffs are not necessary between every column, they just show work moving from one phase to another. With Backlog’s custom status feature, it’s easy to map your unique workflow—here are some examples:

- Individuals or Small Teams: Projects | Planning | In-progress | Done

- Dev/IT: Backlog | Pending | Design | Development | Testing | Done

- Design: Backlog | Ready to Start | Design | Sign-off | Done

- Product Management: Features | Pending | Development | Testing | Sign-off | Done

- Marketing: Campaigns | Planning | In-Progress | Done

- Sales: Leads | Initial Outreach | Evaluation | Negotiation | Closed (Won/Lost)

2. List the kinds of work it processes

The next step is to identify the types of work that move through your workflow. Depending on the type of work you do, there may be many kinds or just one. For instance, the primary type of work that flows through a salesperson’s process is “deals.” A developer, on the other hand, will process many different types of work, including “requirements,” “features,” “bugs,” “maintenance,” and so on. If several different kinds of work move through your workflow, you might find it useful to color-code them for easy visibility. You might also consider implementing horizontal “swim lanes” to distinguish between distinct projects or types of work.

3. Create a process for adding new work to the system

Teams typically use a backlog to collect upcoming tasks, which they can then pull into the input queue at regular intervals—this is part of keeping WIP as low as possible to maximize throughput, which we’ll discuss further in the next section. What you call your input queue is up to you—“ready to start,” “pending,” or “planning” are all good options—what is important is that you create a protocol for adding new work to it. Ask:

- How often will we replenish the input queue?

- Who decides what work should be added to it?

Many teams have regular prioritization meetings to add new tasks, but how and when you replenish your queue is up to you.

4. Define classes of service

“Classes of service” is just Kanban terminology for work prioritization—just like first class and economy on an airplane. Teams typically have a “standard” class of service for routine tasks and an “urgent” class of service that expedites important or time-sensitive ones through the workflow.

Respect your process

The great thing about Kanban is that it isn’t a software development lifecycle methodology or a project management framework—rather, it’s designed to work in tandem with other systems. If your team is already practicing Agile, Scrum, DevOps, or another framework, Kanban can give you greater insight into your existing process and illuminate areas of improvement. For instance, if you’re already using Scrum, you can use a Kanban board to host your backlog, plan your sprints, and track the progress of tasks throughout your sprint process. The key is to focus on optimizing these existing processes rather than swapping them out for new ones.

Get your WIP into shape

The next phase of Kanban is to limit WIP. In order to prevent partially-completed work from piling up, you need to limit the total amount of WIP in the system. Here’s how:

Match input to throughput

A team should be able to complete all work items in the input queue in a given time period. For instance, if you replenish your input queue with new tasks from your backlog on a weekly basis, your queue size should be the number of tasks you can complete in a given week.

Set column limits to enforce single-tasking

At least to start with, set each column limit to the number of people available to complete that kind of task. For instance, if a team has three developers, the “development” column should have a WIP limit of three so each developer can work on one task at a time. If a column reaches its limit, no new tasks can be started until a space is cleared by the completion of a task.

Use queues to maintain flow

To absorb the variations between tasks and ensure smooth flow, teams can add “queues”—column sections that show completed work that is ready for the next stage. You can put the queue directly after a completed step (“done”) or directly before the next one (“ready”), the effect is essentially the same. Queues should also have limits to avoid creating excess WIP. They typically look something like this:

Adjust as needed

Above all, Kanban is a process of experimentation and learning. WIP or input queue limits are never set in stone. “You can select a number and then observe whether it is working well,” says Anderson. “If not, adjust it up or down.”

Eliminate unnecessary work

After you’ve been practicing Kanban for a while, you might notice that some tasks end up sitting in your backlog, never high enough priority to make it into your input queue. After a certain amount of time has passed (6 months is a good benchmark), delete these tasks. If they end up becoming important later on, you can always add them back into your backlog.

You might find that reducing the amount of WIP feels uncomfortable at first and might even cause pushback from team members or managers. Anderson recognizes this—and encourages teams to lean into this tension. “The tension created by imposing a WIP limit across the value stream is positive tension,” he writes. “This positive tension forces a discussion about the organization’s issues and dysfunctions.” Take the reduction of WIP as an opportunity to examine the deeper issues at play and discuss solutions.

Practice kaizen

Like most good things, Kanban takes time. In fact, Anderson’s first Kanban experiment at Microsoft took fifteen months to enact. Have patience with the process.

Since Kanban spurs gradual transformation, it’s not always easy to see your advancement day-to-day. It’s important to keep tabs on your headway to drive your motivation and recognize opportunities for further development. You can use the following guiding questions as a starting point to assess your progress:

- Cumulative flow—are the number of tasks across columns generally stable?

- Lead time—how long does it take an item to get from order to completion?

- Due date performance—if tasks have specific deadlines, are they meeting them?

- Throughput—how many items make it through the system in a given time period? (ie. one month)

- Issues and blocked work items—how well is the team identifying, reporting and managing stopped tasks?

- Flow efficiency—what is the ratio between lead time and touch time (time spent working on a given task)?

- Initial quality—what is the defect rate (percentage of work completed that escapes with some kind of issue)?

- Failure load—how many tasks need to be completed as a result of earlier defects or failure to anticipate project needs?

What matters is that you’re continuously improving, little by little. Small changes compound into big results.

Yes we Kanban

Kanban is a simple system with powerful results. Crucially, it doesn’t force teams to change their work habits—it allows them to be unique and become the best they can be through incremental change. David J. Anderson puts it best when he says:

“Kanban is giving permission in the market to create a tailored process optimized to a specific context. Kanban is giving people permission to think for themselves. It is giving people permission to be different: different from the team across the floor, on the next floor, in the next building, and at a neighbouring firm. It’s giving people permission to deviate from the textbook.”

Ready to get started with Kanban? Backlog’s Boards feature makes it easy for teams to manage complex projects using their existing systems. These virtual Kanban boards plug into Backlog’s sophisticated project management and version control platform, allowing team members to manage their projects—and their code—from one centralized location. Get started for free.

Further Reading & Recommended Resources

Kanban

- David J. Anderson’s definitive book, Kanban, is a must-read for Kanban enthusiasts

- There’s a fun Kanban game you can play to learn the system

- Kanban blog provides great tips and tricks for Kanban practitioners

- Kanban University is also a great resource—their “10 Things You Should Know About Kanban” is particularly informative

Just-in-Time and the Toyota Production System

- Toyota explains the TPS

- The origin story of just-in-time

- All about Taiichi Ohno